There are three words critical to understanding Roger Kimball’s “Restoring American Culture” essay in the Imprimis, February 2025 issue: common sense, culture, and civilization.

Unfortunately, Kimball never defined them.

It was a provocative essay – one that makes you think. The piece was adapted from his talk last January at Hillsdale College, the people who produce Imprimis.

Kimball has credentials. He is editor and publisher of The New Criterion, a New York–based monthly literary magazine and journal of artistic and cultural criticism. He earned a B.A. from Bennington College and an M.A. and M.Phil. from Yale. He is a published writer in outlets like The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times Book Review, and is a columnist for a couple of outlets. Finally, he authored or edited books, like The Long March: How the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s Changed Americaz.

In other words, he’s been around and knows a thing or two. So he deserves to be listened to.

Which is why I was surprised his essay was almost incoherent. I’d like to explain my point of view.

My credentials are not as expansive as Kimball’s. I started and grew to a successful 25-person marketing agency in 1990 that is still standing despite all the disruptions, have a B.A. and M.A. from Lewis University and DePaul University respectively, and have published many articles in the trade journals and research journals over the years in my area. I also taught high school for ten years, and am now Reading with Jimmy, trying to point out that reading the classics is how you succeed in life. Perhaps I don’t deserve to be listened to; but then, perhaps I do, especially since I (and probably Kimball) read Aristotle who taught us to define our terms if we’re going to communicate successfully. You don’t write an essay or give a speech like this (or write a blog like I’m doing) unless you want to communicate with your fellow human beings.

Starting Gate

He begins his essay agreeing with Trump’s declaration, “We will begin the complete restoration of America and the revolution of common sense. It’s all about common sense.” Then he quotes Descartes ( of “Cogito ergo sum,” fame) who reportedly said, common sense “was the most widely distributed thing in the world.” Kimball challenges that statement by saying Descartes wasn’t aware of “the of 21st century America. If he were with us today, I am sure he would emend his opinion.”

Then he launches into some very challenging examples of what is NOT common sense.

“After all, is it common sense to pretend that men can be women? Or to pretend that you do not know what a woman is? During her confirmation hearings, a sitting member of the Supreme Court professed to be baffled by that question.”

He’s referring of course to Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson’s statement when examined by the Senate that she didn’t know what a woman was…that she wasn’t a biologist. And while provocative, there is no clear definition of “common sense” in this statement.

This example also highlights a pattern: Kimball uses strong rhetoric without clarifying the baseline meanings behind his critiques.”

Kimball leaps to culture, saying: “In the cultural realm, is it common sense to celebrate art that is indistinguishable from pornography or some other form of psychopathology?” He ends up defining culture as “we know it when we see it.” This is the same definition he uses for civilization when he refers to Kenneth Clark’s question of what civilization is: “I don’t know. I can’t define it in abstract terms, but I can recognize it when I see it.”

And therein lies the problem: all of us don’t see things the same way. That’s why you have to define your words – to get the baseline for understanding.

I’m color blind. In my blog “The problem with dots” I explained how this condition impacted my advertising career, where I learned to see what other people see as RED or GREEN. But when asked what I see, it was impossible to explain, as I had no basis of comparison.

So when people say things like “I know it when I see it,” I have to probe further because frankly, not everyone sees the same thing the same way.

For example, you can “see” Jackson’s statement that she doesn’t know what a woman is because she’s not a biologist as not common sense, but then, you an also see it as a true statement if you think about real definition of “woman.” Her “choice” not to define it is more of a tell because she is one (I think). But is her answer NOT common sense, or is it absurd? Or something else? I can’t even conclude she was “pretending” – can you?

Common Sense

I like to look at “common sense” as two separate words: common is the adjective modifying sense. Therefore, sense is what we’re really talking about: “Does it make sense?” You can have “perfect” sense. In that light, Jackson’s statement doesn’t make sense, so it should be classified as nonsense. Hmm…why didn’t anyone point that out during the hearing?

I like to look at “common sense” as two separate words: common is the adjective modifying sense. Therefore, sense is what we’re really talking about: “Does it make sense?” You can have “perfect” sense. In that light, Jackson’s statement doesn’t make sense, so it should be classified as nonsense. Hmm…why didn’t anyone point that out during the hearing?

We have five senses. If we define “sense” we see “a faculty by which the body perceives an external stimulus; the faculties of sight, smell, hearing, taste and touch.” The word is also “feel that something is the case” as in “she had the sense.” I already pointed out some of these senses can be limited (color blind).

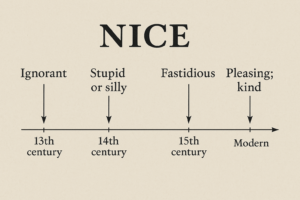

The word “common” on the other hand is defined as “occurring, found or done often; prevalent.” Or, “shared by, coming from, or done by more than one.” Or, “not rare.”

I have always found definitions to be a good starting point for understanding myself and others, but nevertheless, difficult to translate what we sense (reality) for the purpose of communicating. Words are, after all, abstract things that convey some type of reality. In which case, “knowing it when we see it” makes some sense after all (no pun intended).

And yet it doesn’t make sense because what you or I sense about something may be totally different. I remember after 9/11 at a client sharing lunch telling a product manager, “I can understand what those guys who flew the planes into the Towers were doing.” He looked at me in shock. I continued telling him, “They believed in something and were carrying out actions based on their beliefs. I’m not saying it was right; I’m just saying it was the same thing the Japanese “Kamikaze” suicide pilots did in World War II: die for what they believed. What anyone who sacrifices their life for something they believe in does. We do that too, don’t we?” The conversation ended abruptly.

In my world, understanding is essential to acquiring the truth, so I’m compelled to understand when Kimball writes an essay like this without clear definitions. Perhaps there are no clear definitions to these words, but stating with definitions would be a great place to begin a discussion besides definitions like “I know it when I see it” which anyone can say at any time about any thing.

Words Matter

Those three words are not the only ones Kimball uses without definition, which seems to be the plague among writers of his ilk. For example, Kimball writes, “These days, the revival of common sense is often opposed to the rule of that coterie of bureaucrats the media calls ‘the elites.’” It’s not Kimball’s fault that words metamorphosize through usage to confuse us. But sometimes using specific words is also a tell about the writer. In this case, “coterie.”

I’m an English major and I never encountered that word in my reading, or if I did, I glossed over it. Coterie means “a small group of people with shared interests or tastes, especially one exclusive to other people.” It’s a network, community, and another word to use in its place would be “tight-knit.” I like the word gang. A writer can select any word he or she wants when they write to describe things. I learned something looking up the definition, but then stumbled at the word “elites” which you hear a lot these days.

Later in the essay he qualifies “elite” with an adjective – “true” elite. But elite itself means “a select group superior in terms of ability or qualities to the rest of the group or society.” It also means “size of letters in typewriting” (remember typewriters?). Adding the adjective confuses the issue because if there is a true, there has to be a false. These are judgment calls, or do I know an elite when I see an elite?

In my blog The Intended and Unintended Consequences of Words, I pointed out the importance of word usage based on what our senses are telling us. I wrote, “Words that are used often have intended and unintended consequences because of what they mean and how they make you feel.” The blog is about my observation about one of the members who was pregnant. This is what happened after I made my observation:

Immediately the room got suddenly silent for a second (there was small talk going on between people). All heads turned to the attorney as if to confirm my observation, then to me. An owner who ran an HR business on my right said to me quietly, but loud enough for others to hear (including the young attorney), “You’re a brave one.” I replied acting innocently, “Brave? What do you mean?” The HR business person laughed awkwardly as her eyes got big, as if to say, “You mean you don’t know what you just did? What if you are wrong?” The young attorney in the meantime acknowledged my comment. “Yes I am,” she said, her blush disappearing, but her smile staying put. “Congratulations,” I replied.

Then some people in the room began a discussion on how making such observations can be wrong, and if they are wrong, turn out embarrassing and rude. I went on:

“But, I wasn’t wrong,” I announced. “Didn’t all of you see the glow around her?” It was the perfect response and spontaneous, the best kind. Sometimes I wonder where these responses come from. The owner of an IT company on my left laughed, leaned toward me to quietly say, “Nice recovery.” “Recovery,” I asked? “But there is a glow around her. Don’t you see it? Doesn’t anyone here see it?” Now the room became completely silent. You could almost see everyone looking hard for the glow around her.

Sensing is very important to the words we use, and vice versa. The words Kimball uses – culture, civilization and common sense – all carry the denotations and connotations I discussed in that blog. Which is why I was so surprised Kimball never defined his terms.

Confusion Reigns

“Abnormal is not normal just because it is prevalent” was another point Kimball brought out. When you first read that sentence, it is hard to argue with it. But here again, what is “normal?” His examples for this sentence were:

- the mutilation of children is not “gender-affirming care.”

- anti-white racism is not “anti-racism.”

- Illegal migrants are not “undocumented ‘new neighbors.’”

- A bisected cow in a tank of formaldehyde is not an important work of art.

Provocative to be sure, but switching words around is making his prevalent argument true or false. Each one of these points requires definitions and a further explanation besides his inference that they are “abnormal.”

The truth is, you can’t tell a “yes” without a “no.” You can’t know what “success” is without knowing what “failure” is. This theory of opposites has been around quite awhile — Heraclitus and Plato probably started the whole thing in the West and the Chinese concept of yin and yang in the East.

The truth is, you can’t tell a “yes” without a “no.” You can’t know what “success” is without knowing what “failure” is. This theory of opposites has been around quite awhile — Heraclitus and Plato probably started the whole thing in the West and the Chinese concept of yin and yang in the East.

But you don’t have to be a philosopher to know this is true. So “normal” has an opposite as abnormal, but as far as prevalent (widespread in a particular area or at a particular time) is concerned, “rare” is its opposite, or uncommon.

The real question is: how prevalent was his abnormal bullet points, and if indeed those bullet points were abnormal. See the power of words? Because that is all those bullet points do is demonstrate the confusion brought about by words that are not defined.

Civilization

Nor does Kimball define Civilization, except by using three examples: 1)Kenneth Clark’s Civilization series, 2)Leonard Bernstein’s Young People’s Concerts and the 3)Book of the Month Club. I’m old enough to remember all three and participate in all three. I think Kimball is saying that today, civilization doesn’t exist based on these three examples, citing that, “all these initiatives bore witness to a culture at one with itself.” The implication is that today our “culture” (whatever that means) isn’t.

Here are some friendly reminders that a culture is never at one with itself based on the dates of his three cited events.

- 1969 in the US was a year of significant events, including the moon landing, the Woodstock festival, the beginning of “Vietnamization,” and the Stonewall riots, marking the start of the modern gay rights movement

- In 1958, the US experienced a recession with unemployment above 7%, the creation of NASA, and the launch of the first US satellite, Explorer 1, among other events.

- The 1930s in the US were defined by the Great Depression, a period of severe economic hardship following the 1929 stock market crash, and the Dust Bowl, a severe ecological disaster in the Great Plains.

Culture is always “in flux” and escapes precise definitions, again because of the senses involved. For example, his broad, sweeping observation leaves a lot to be examined:

Today, we are living in the aftermath of that avant-garde: all those “adversarial” gestures, poses, ambitions, and tactics that emerged and were legitimized in the 1880s and 1890s, flowered in the first half of the last century, and live on in the frantic twilight of postmodernism. Establishment conservatives have done nothing effective to challenge this. On the contrary, despite little whimpers here and there, they have capitulated to it.

Some big words in that statement (i.e., avant-garde, postmodernism, conservatives), but do you know for example what “avant-garde” means? It means “new and unusual or experimental ideas, especially in the arts, or the people introducing them.” I can’t think of a time where this doesn’t apply (i.e., I would call AI Avant-garde?).

Such a broad brushstroke isn’t really healthy to prove a point about common sense, culture or civilization.

Trump

I think Kimball admires Donald Trump when you read his essay, but he might be afraid to come right out and “endorse” him. For example, the whole essay is a kind of testimony to Trump, from the first paragraph to the last. He ends his essay like this:

The spectacle of Donald Trump’s boundless energy, and the energy he calls forth from others, is heartening. Among other things, it makes us appreciate how his “revolution of common sense” might not only spark a political restoration, but also a new cultural golden age.

I don’t know if Kimball watched Trump’s ascension into politics but very early when he was running for the first term, I remember Henry McMaster, now governor of South Carolina who was the lieutenant governor at that time called Trump “a force of nature.” I never forgot those words as I watched Trump’s career unfold.

Whether you support him or not, Trump’s impact on cultural and political discourse is undeniable. My own word for President Trump is catalyst. Its definition? “A substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction without itself undergoing any permanent chemical change.” You need only look around him to understand the truth of that statement.

Words do matter. So I don’t know if Kimball thinks Trump is going to “restore” American culture since he never defines it, nor common sense, nor civilization, but I think I know what he is talking about. And while I’ll always listen for the truth in voices like Kimball’s, I still believe our culture is too diverse, too layered, and too alive to be restored by slogans or seen with one set of eyes. We must do the harder work: defining what we mean, and seeing what others see.

And then tell each other what we see when we see it. Or try to at least.