I had agreed to submit my paper to Dr. Murphy as the other professional medievalist on the DePaul faculty because Dr. Kelly found it impossible to “provide an objective grade.” This is his evaluation, including the scanned original at the end with some editorial comments. Note the mis-spelling of my name in his title. Always a tell.

_____________________________________________________________________

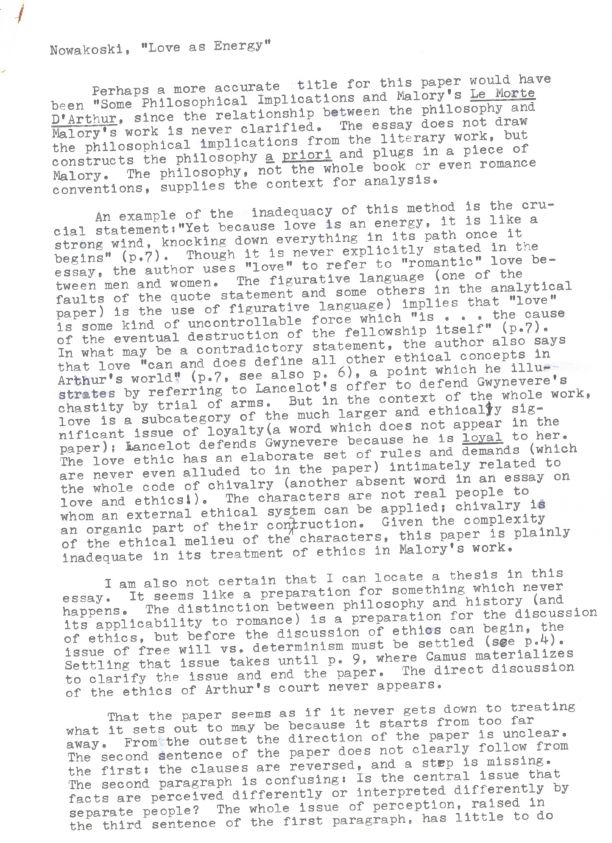

Nowakoski, “Love as Energy”

Perhaps a more accurate title for this paper would have been “Some Philosophical Implications and Malory’s Le Norte D’Arthur, since the relationship between the philosophy and Malory’s work is never clarified. The essay does not draw the philosophical implications from the literary work, but constructs the philosophy a priori and plugs in a piece of Malory. The philosophy, not the whole book or even romance conventions, supplies the context for analysis.

An example of the inadequacy of this method is the crucial statement:”Yet because love is an energy, itis like a strong wind, knocking down everything in its path once it begins” (p.7). Though it is never explicitly stated in the essay, the author uses “love” to refer to “romantic” love between men and women. The figurative language (one of the faults of the quote statement and some others in the analytical paper) is the use of figurative language) implies that “love” is some kind of uncontrollable force which “is . . . the cause of the eventual destruction of the fellowship itself” (p.7). In what may be a contradictory statement, the author also says that love “can and does define all other ethical concepts in Arthur’s world” (p.7, see also p. 6), a point which he illustrates by referring to Lancelot’s offer to defend Gwynevere’s chastity by trial of arms. But in the context of the whole work, love is a subcategory of the much larger and ethically significant issue of loyalty(a word which does not appear in the paper); Lancelot defends Gwynevere because he is loyal to her. The love ethic has an elaborate set of rules and demands (which are never even alluded to in the paper) intimately related to the whole code of chivalry (another absent word in an essay on love and ethics1). The characters are not real people to whom an external ethical system can be applied; chivalry is an organic part of their construction. Given the complexity of the ethical melieu of the characters, this paper is plainly inadequate in its treatment of ethics in Malory’s work.

I am also not certain that I can locate a thesis in this essay. It seems like a preparation for something which never happens. The distinction between philosophy and history (and its applicability to romance) is a preparation for the discussion of ethics, but before the discussion of ethics can begin, the issue of free will vs. determinism must be settled (see p.4). Settling that issue takes until p. 9, where Camus materializes to clarify the issue and end the paper. The direct discussion of the ethics of Arthur’s court never appears.

That the paper seems as if it never gets down to treating what it sets out to may be because it starts from too far away. From the outset the direction of the paper is unclear. The second sentence of the paper does not clearly follow from the first: the clauses are reversed, and a step is missing. The second paragraph is confusing: Is the central issue that facts are perceived differently or interpreted differently by separate people? The whole issue of perception, raised in the third sentence of the first paragraph, has little to do with the history-poetry distinction of the beginning of the paper. Since, as the author acknowledges, history and poetry served much the same function in the middle ages, why bring the distinction up?

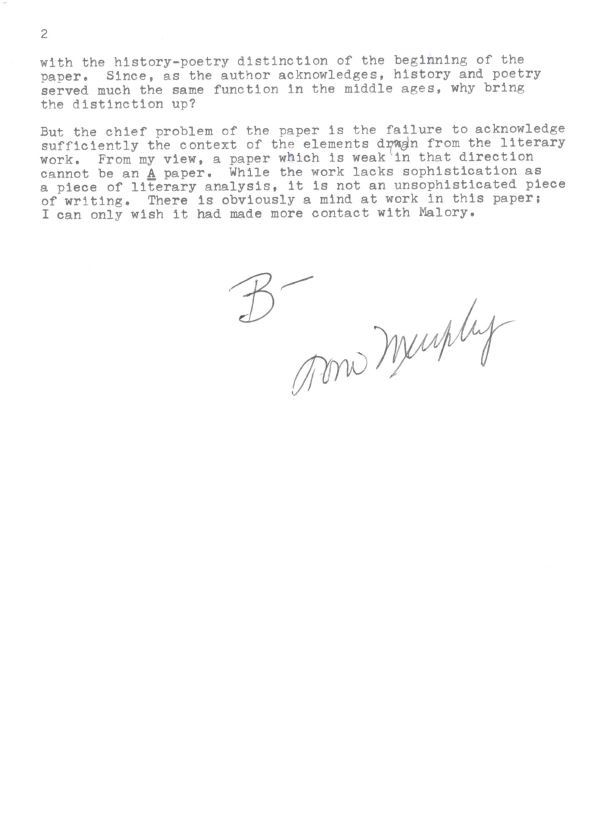

But the chief problem of the paper is the failure to acknowledge sufficiently the context of the elements drawn from the literary work. From my view, a paper which is weak in that direction cannot be an A paper. While the work lacks sophistication as a piece of literary analysis, it is not an unsophisticated piece of writing. There is obviously a mind at work in this paper; I can only wish it had made more contact with Malory.

B-, Tom Murphy

______________________________________________________________________________

Here are the original scanned pages of Dr. Murphy’s response.

______________________________________________________________________________

Some comments follow on Dr. Murphy’s response. I never responded to his critique. I just accepted my fate. Ironically, like Merlin, I was able to “see the future” when this whole thing started. It came true. I graduated, but not with honors. Below are some comments from 2022 having re-read everything again for this posting.

______________________________________________________________________________

The basic charge by Dr. Murphy on the paper is this: he says I “construct the philosophy a priori and plug in a piece of Malory.” That, “the philosophy, not the whole book or even romance conventions, supplies the context for analysis.”

My title, by the way, nullifies this charge perfectly. Here is additional thinking.

Using Latin phrases in a critique is always interesting. He says I construct the philosophy a priori. The Latin means “knowledge independent from current experience.” The other kind of knowledge is called a posteriori, which is knowledge from experience. I’ve always had a problem distinguishing them in terms of knowledge. Many philosophers argue a lot about the words (Kant, etc.). Some people say math is a priori, you don’t need experience to have that type of knowledge. But someone had to teach you 2+2=4. You had to experience it, so that might mean the knowledge is the a posteriori.

It really doesn’t matter, does it? As Camus, who Murphy said “materializes to clarify the issue and end the paper,” said: “It’s not the soundness of the argument, but that it make you think that’s important.”

When I read Malory, I had to read it as me — that is, bringing my experience and knowledge with me so when I read it and started to see philosophies emerge, the title of my paper expressed this: “some philosophical implications.” I read it as a novel — not as history. I read it as I had been taught: as a world unto itself. I was trained not to allow outside influences affect the world of a book; who cares what Dostoevsky experienced that brought the intensity of characters to his novels?

Murphy noted: “The paper seems as if it never gets down to treating what it sets out to may be because it starts from too far away.” My previous mentor — Father Larkin who taught me Renaissance and actually convinced me to finish my degree — told me about my writing, “You take a long wind up.” He referred to my introductions. I have always done that (my long copy bias). And while I learned to shorten copy as a copywriter, language always intrigued me, and using it to explain what was going on in my head, well, a challenge. But again, it will be up to the reader to determine if I ever got down to treating what I set out to do if they are intereseted.

I noted, too, that Murphy devoted a big second paragraph talking about the “inadequacy: of my method in discussing love. His curious comment, “Though it is never explicitly stated in the essay, the author uses ‘love’ to refer to ‘romantic’ love between men and women.” is interesting because I wouldn’t know or see any other way to see what those characters were acting as “love.” And I never said it “explicitly” because it wasn’t the intent: the love I saw was not necessarily between men and women.

Indeed, his charge that I ignored the whole code of chivalry is also curious: Lancelot’s offer to defend Gwynevere’s chastity by trial of arms which he acknowledged I used to illustrate love as a uncontrollable force is the prime example of chivalry.

Frankly, when you add up some of the comments from Murphy, I’m surprised the paper got a B- from him, the exact same grade Kelly gave me. I would have flunked the guy who wrote this if I really believed all the they did about this paper. Wouldn’t you?

No, I’m not giving my Masters Degree back!