Sun Tzu said that “In war the victorious strategist only seeks battle after the victory has been won, whereas he who is destined to defeat first fights and afterwards looks for victory.” This is often interpreted as “Every battle is won before it is ever fought.” You can debate the meaning, but it really says you have to think things through before you do battle. I didn’t know about Sun Tzu when I was going for my Master’s degree, and consequently, didn’t follow this good advice. My strategy, if I wanted to graduate with distinction, would have been totally different than what I executed. I may have just wanted a fight. I’ve always enjoyed a fight. I just read “At 75, he still wants to fight everyone this week,” Notre Dame coach Mike Brey, a former Duke assistant, told CBS Sports about Mike Krzyzewski. In any case, it was a deep experience and left me with the lesson: if you are going to fight, strategy is most important before you throw the first punch. In other words, always be thinking. Which Sun Tzu also taught me subsequently: “Ponder and deliberate before you make a move.”

___________________________________________________

Setting the Stage.

It was clear from me after attending the first class that this course was going to be boring. I had almost quit going for the degree half-way through the program (six courses of 12) because I was already teaching, and had prepared myself for teaching by taking every elective in English that I could at Lewis University as an undergraduate. I was bored at DePaul. I was bored actually, if ready my journals when I publish them, during most of my schooling.

I stumbled on a remarkable man in one of those six courses: Father Jim Larkin. When I took a course with him, I scheduled a meeting to discuss my paper and told him about my dilemma. He said, “Why quit? You know you can’t grow on the pay scale unless you move up the ladder with another degree. Take ten courses here at DePaul instead of the 12, and write a thesis.” I asked what I would write about, and he said he would be going to England later that year and he would bring me a manuscript. The thesis would be about that manuscript. “So you take a few more courses, do the thesis and there you are,” he said. “You’ve got the talent.”

It was an offer I couldn’t refuse. The thesis was based on the manuscript Father Larkin brought back and I titled it, “The Refugee or the School for Constancy: an Edition with Introduction and Notes.” It was presented to the Department of English at DePaul in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts, and it was accepted. I’m looking at my copy now, as I write this. To this day, you can find it probably in the DePaul library. It was published in 1976, and based on text in the British Library (MS 25998), comprised of 119 pages of fairly legible 18th century script.

I took a few more courses with Father Larkin, and took the comprehensive exams required for the degree. These exams were comprised of four, two-hour tests you had to take over the course of a couple of days. I passed all four, two of them with “distinction” — in Renaissance and American Literature. American Literature I had not had courses in at the graduate level. My work at Lewis University was steeped in American Literature.

I had one more course to take to meet the 10-course requirement, so I asked Father Larkin for his guidance. He said Dr. Kelly has a course in Arthurian Legend. “I heard some good things about her, but I don’t know her personally.”

From the first session with Dr. Kelly, I knew it was the wrong decision. Kelly rambled in her teaching style and was the exact opposite of a Larkin and other superior instructors I had had as an undergraduate.

It wasn’t that she talked “above” students; I had been in courses before where the instructor talks “above” the students and brings you up to a higher level. This was not one of them. Dr. Kelly rambled, talking about her trips to England, drifting off into areas that frankly had nothing to do with Arthurian legend.

Nevertheless, I stayed. Half way through I remained after class and talked to Dr. Kelly about my desire to get an A and graduate with distinction. It was a fatal error.

I said, “Dr. Kelly, I was wondering if I might ask you something.”

“Of course,” she said.

“This is my last course before I graduate, and if I can get an A, I would not only graduate: I would graduate with distinction because of my grade point average. So I was wondering, if I were to give you my paper ahead of time, would you be kind enough to guide me in areas you might feel need any further development so I can achieve that grade? I’ve already been working on it for several weeks, and am confident in the direction. I just want your input if that’s possible ahead of time rather than waiting until final submission. Would that be acceptable?”

She looked at me for a moment questioningly, but said, “Of course.”

I smiled. “Thank you very much, Dr. Kelly” I replied. “Here is it.”

She again looked surprised, took the paper, and I left the room.

This was, as I mentioned, a fatal error, and I would not get my A. But I didn’t know it at the time. It was an error because 1 )I caught her off guard, and 2) how could anyone have a paper completed half way through a course. I didn’t know these things. I totally overlooked the ego of a professor, which I learned is in not only professors, but in many business executives.

I was so eager to not only be the first Nowakowski to graduate with an advanced degree, but the first to graduate with “distinction.”

The following week, she walked up to me before class (I always sat in the back of the room) and handed me the same envelope with my paper in it that I had given her the week before. She looked at me smiling, handed me it to me and said with assurance, “I don’t think you’ll be too happy with this.”

Then she walked back to the front of the room and began conducting class.

I opened the envelope and look at the five pieces of notebook legal paper, hand written notes along with my paper, which had no marks on it. I started reading her comments, and I sank in the understanding of the error I had made last week. Every sentence she wrote (you can see the original scanned at the bottom of the the review Kelly’s comments to Nowakowski.

Throughout her lecture she made references to people in class who think they are at a graduate level but really don’t belong in this class…that she finds it hard to believe that some people have made it through to almost graduating with the kind of shallow thinking they bring to a topic like Arthurian legend.

These comments, of course, were all directed at only me, and only she and I knew they were because she would look directly at me every now and then when she issued the cutting remarks. People in class looked at each wondering what in the world, or who in the world, she was talking about. She rambled about this and that. It was a very personal attack, but done in a way that no one except me knew she was doing it.

Brilliant, actually. But she knew, and I knew. This type of situation was to repeat itself later in my life — a situation where I knew the truth, but no one else around me did. But those are other stories.

When things like this happen, they are intense moments of introspection. They make you wonder if you just plain stupid…that somehow, you made it through with luck, not your intelligence. It is truly self-deflating.

I felt shattered as I drove home after class. I swore out loud, as I reasoned it through. No, I wasn’t stupid. No, it wasn’t luck. I determined to examine the situation more closely.

My Response to Kelly.

I thought about the situation a lot. I re-read her criticism. I had to decide what to do: comply with her charges and guidance, or take a stand and leave the paper “as is.”

I read the paper again, carefully. Then I reread what she said and made the decision: my paper would have to stand “as is.”

As I shaped my response, I took care to answer all of her charges, one by one. I spent time making sure of the response. Then I decided to counter attack. I decided since she took me apart personally in those notes about my paper, I might as well have a shot or two at her. So I did.

When and if you read my response, you can see for yourself.

As I said, if I wanted the A, this was not the way to get it. But I figured what the hell, I’ll still graduate (I hoped), but it wouldn’t be with the distinction thing.

I read the response to my wife, and she asked if I really wanted to do that. My wife is my lifeblood, my stability. She is always there for me, as I am for her, and in spite of me being so weird, she stick with me. I said, “I don’t see that I have a choice. She is saying I’m stupid. And I’m not. Not in this case.”

When I told her what I’m doing now on this website– documenting this episode in my life — she said, “Can’t you just get over it?”

Great question.

But it’s not a matter of getting over it. I was over it when the final outcome emerged, which is that I didn’t get the A. I was over it when I decided to attack Dr. Kelly besides submit my rebuttals to her charges.

But episodes like this can shape other’s decisions when conflict arise. The thing you have to learn from this is that if you challenge power, you have to have a certain amount of power if you expect to win. Isn’t that a law in physics of some kind? An object travels in a straight line unless acted on my some other force? It depends I guess how much force is exerted on the thing coming at you.

I knew from the beginning I wouldn’t be able to win this fight once it started, but like I said, once you’re in it, you’re in it.

I also really wanted to see what would happen. That’s what life is about, actually, seeing what happens as a result of any action you take. You just have to be prepared for outcomes to your actions. And since you don’t know what will happen when you initiate an action all the time, you have to be able to live with the outcomes. I was. I did.

The Registered Letter from DePaul.

My class with Dr. Kelly was on Saturdays. On Wednesday following class where I handed my response, I received a registered letter (scanned at the bottom) from Dr. Kelly. It said, “At the present time I am unable to provide an objective grade for you in English 410. Whatever grade I might give you could be construed as the result of either intimidation or prejudice.”

I stopped reading for a few seconds, but continued. “To find some reasonable resolution for this dilemma, I asked Dr. Ewers if I could submit your paper to the other professional medievalist on our faculty, Dr. Thomas Murphy. Since you returned the paper to me, I assume it represents your final submission. Before I give the paper to Dr. Murphy for evaluation, I need a written statement from you, agreeing to accept Dr. Murphy’s grade as your grade for the course.”

It closed: “Should you object to this arrangement, I would suggest that you contact Dr. Ewers with any alternative suggestion you may have. I shall retain your paper, the xerox of my comments, and your refutation. In the event that some mutually agreeable solution cannot be reached, I will turn these over to the Dean of the Graduate School for arbitration.”

I remember turning to my wife when I read that letter saying, “Jesus …the Dean of the Graduate School for Arbitration. Just what I need.”

My father had just died. He was 50 years old. I decided I would contact Dr. Ewers and made an appointment. Ewers was the chairperson of the English Department, and I knew her. In fact, she had been a “guest” lecturer in Dr. Kelly’s class one day to talk about Arthur. I thought at the time Dr. Kelly had run out of material and needed a break. A filler.

But I have to admit, now, that I was really sort of happy inside. I was in a fight — a real fight, with real consequences. It was like a chess game. And like I would learn years later reading Sun Tzu, I had already seen the outcome of this battle: I would lose. There was nothing for me to do now except play it out.

Of course, I could have gone to the “Dean for arbitration,” but in those days, it really wasn’t done that way. You were the student, the teacher was the teacher. As the years rolled by and authority loosened up, maybe it would have turned out differently. In any case, I went to see Dr. Ewers.

When I sat down in her office, I said, “This is not what I wanted, this arbitration thing. But did you read my paper and her charges and my rebuttal?”

“Yes,” she said. “I read everything.”

“You know if I go along with this Murphy idea, it’s not going to be in my favor,” I told Ewers. “I’m a teacher. I know how teachers are. They stick together like lawyers. I won’t get the A.”

She smiled. “You don’t know that,” she said. She paused, and then added, “You know, this is not the first time this has happened in her class. You’re not the first one.”

I felt surprised and suddenly kinda glad, so I smiled. “I see,” I replied. “Then what am I supposed to do? If this has happened with others, and I’m not the only one to be feeling like this over my work and her judgment of that work, what would you recommend? What did others do?”

“You have to make your decision,” she said. “It is up to you. When these things happen, it’s always uncomfortable. I can’t tell you what other people did.”

“But you read my paper and her comments, right?” She nodded yes. “Then?”

There was silence.

“You know, Jim, when I was lecturing in her class that day, you were the only one in the class — the only one — that I felt I wasn’t reaching with my lecture,” Ewers suddenly admitted.

“What do you mean?” I asked again surprised by such a comment out of nowhere.

“I mean you were the only one I wasn’t getting verbal or physical cues back that you understood what I was talking about.,” she continued. “You sat in the back of the class, you would look at me now and then expressionless, or you would look out the window, you took notes or wrote something down from time to time, but I didn’t get any positive feedback from you like I did the others.”

“You mean like the nodding heads?”

She smiled. I continued, “That’s my nature,” I said. “I really don’t respond like other people. I listen. And then I write in my journals. Or in my notebooks. I took copious notes. I always do that.”

I proceeded to repeat what her lecture was about back to her. I spoke about three minutes, as her eyes widened with each sentence that reflected the content of her lecture around Arthur.

“I see,” she said now as surprised as me how this conversation swung around somehow. “So it’s obvious you are a smart guy. So what made you challenge her? Why didn’t you just give her what she wanted to get your A?”

“You said it just now yourself,” I replied. “If I’m not the first to challenge her, and I won’t be the last, it’s obviously not about me. She’s obviously not that smart. I teach underachievers. You can’t fake your passion for learning, and you can’t show slides of your trip to England and call that education, even if you say you traveled over the roads Arthur in theory did. Who cares. Besides, my paper speaks for itself. You read it. I re-read it. I could dilute it along one of the lines she suggests, but why do that if it can stand on it’s own. It’s worth the A, isn’t it?”

“But you asked her for her feedback,” Ewers said. “And she gave it to you. Now you’re saying you don’t want to take it.”

“But you read her feedback,” I replied. “She made me feel somehow like I cheated everyone at DePaul by lasting this long in graduate school. She’s not comfortable in her own skin and is letting that discomfort show through. I don’t think she understood what I was talking about quite frankly.”

There was silence again, and I let it sit for a bit.

In any encounter, there is “the” moment — the one where you have to make the split second decision that will determine the outcome of the engagement. This was that moment. All sorts of thoughts crossed back and forth in my mind, but I already knew going in what I would do if things went along these lines. I had played it out several ways, and had decided when I walked into the office what the outcome would be. I didn’t know it, but I was already practicing Sun-Tzu philosophy.

“I’ll go with the Murphy thing,” I said. “But you and I both know how it will turn out.”

She smiled again, “I can’t say I do, but I understand. Good luck.”

“So, what did you think about my paper?”

She said smiling, “It was, different.”

I smiled back, understanding, and left.

“Different” is one of the safest words in the English language. You can find Dr. Murphy’s response to my paper in another section of this website.

Moments

Life is comprised of moments. People like to focus on the ones that change their lives.

But the fact is, every moment you have changes your life. The joy of living is in the knowledge that each of those moments means something, changes you, shapes you. And, it’s up to you to define that “something.”

At dinner a few weeks ago with Peter and Pat, a married couple we met at the local YMCA, Peter started telling me about the “butterfly effect.”

“You’ve heard of that?” he asked.

“Of course,” I said. “And it’s true.”

He looked at him puzzled. So I gave him an example. I told him the story of how I was fired for defending a student. Two days before term started, I got the call that “You can’t come back.” The principal didn’t make the call. The chairman of the English department didn’t make the call. They had the department secretary make the call. When you have no job two days before school starts, you can’t start handing out resumes. I found three part-time jobs within a week: teaching a couple of classes at Lake County College in Illinois, stringing for the local newspaper, and writing PhD dissertations for a guy I found answering an ad for writers in the Chicago Tribune.

I hated the principal for several years: he had shaken my hand at the end of the term before summer and said, “Look forward to seeing you next term” and handed me the paycheck. I thought, “He’s human.” Because of the blowup that happened when I defended Ron S. from his outburst over not publishing the hockey club picture in the yearbook (yes, that is what the issue was, the student wanted to buck the system and print the picture of the hockey club though not sanctioned officially by the school). The principal (Nike M.) was like a madman, ripping Ron until the kid was shaking, in tears. I put a stop to it by telling the principal to stop. He, too, was shaking with anger. “Look, it won’t be in the book, OK? There’s not need to berate the kid. I’ll make sure it doesn’t appear.”

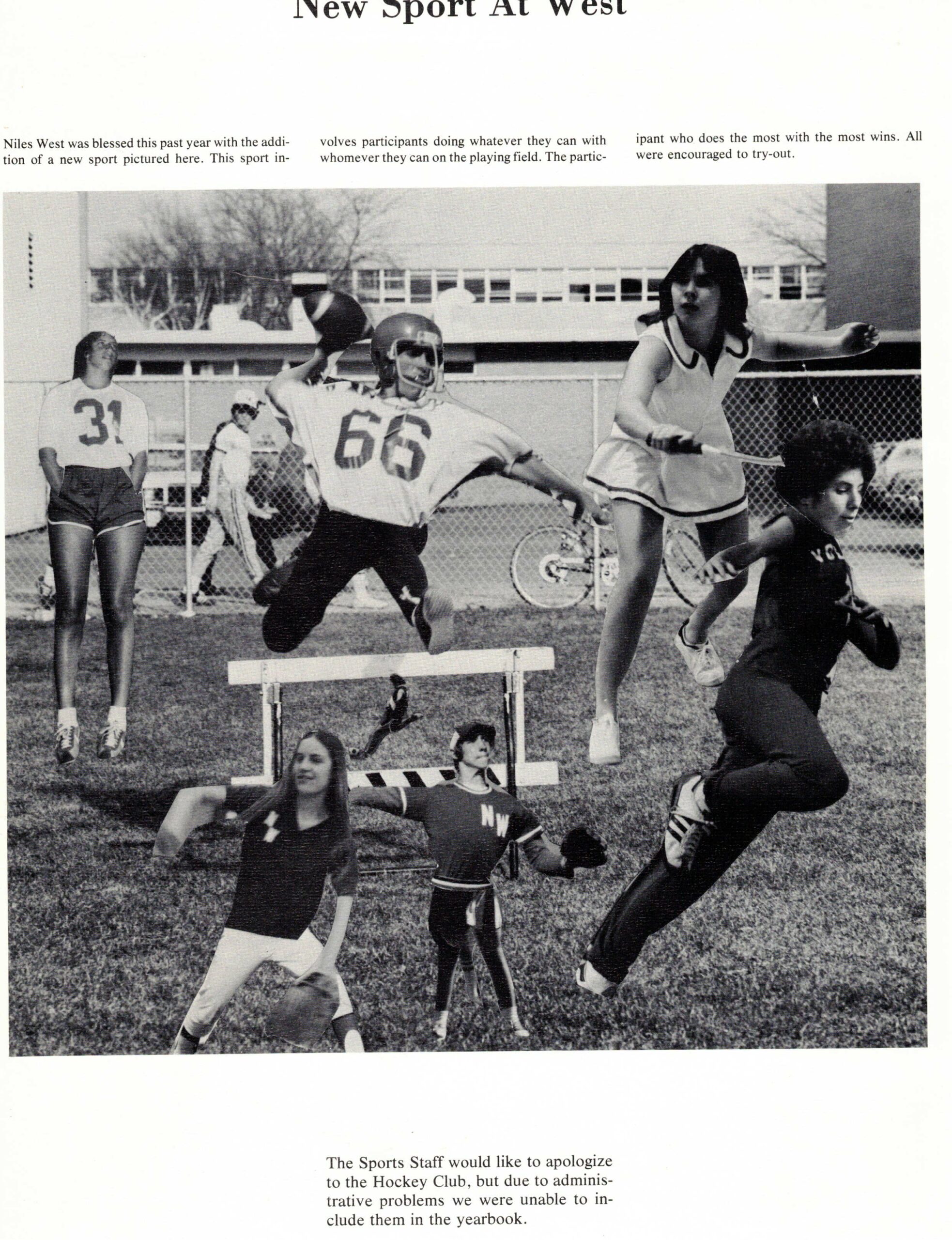

We left and Ron didn’t know what to do. I told him to make up a picture, a collage and he did: “New Sport at Niles West.” I scanned it below. But what Ron didn’t tell him is that he slipped a paragraph on the bottom before it went to press. When I saw that paragraph, I realized that’s going to it for me. I call Ron and he said proudly, “He can’t do anything to me, I’m graduating.”

“It’s no you he will do something to, it’s me.”

“But you didn’t do anything. I did,” he said.

“That doesn’t matter. I challenged him. You challenged him. He can’t touch you, he will go after me.”

Which is why when he shook my hand at the end of term and said what he said I thought he was human. I was wrong.

I told Peter this story and said I often thought of writing Nike a letter of thanks, because if he didn’t do that, I wouldn’t be sitting here at dinner with Peter and is wife and my wife. That moment changed everything, as subsequent moments changed everything. You simply have to examine your own moments and trace their influence. Sometimes, like this, a moment can have profound impact you can see and feel. Other moments pass by unnoticed. But both have effects on your life. The point is, after all, to live the moment to its fullest, no matter what you are doing. Winning — or losing.