One week after I received Dr. Kelly’s comments, I returned to class with my own envelope. Inside was my original paper, and the following 6-page rebuttal to her charges. Before class began, walked up to her desk and handed her the envelope, saying “I don’t think you’ll be too happy with this.” The transcribed from the original (which has been scanned at the end of this document) is below:

______________________________________________________________

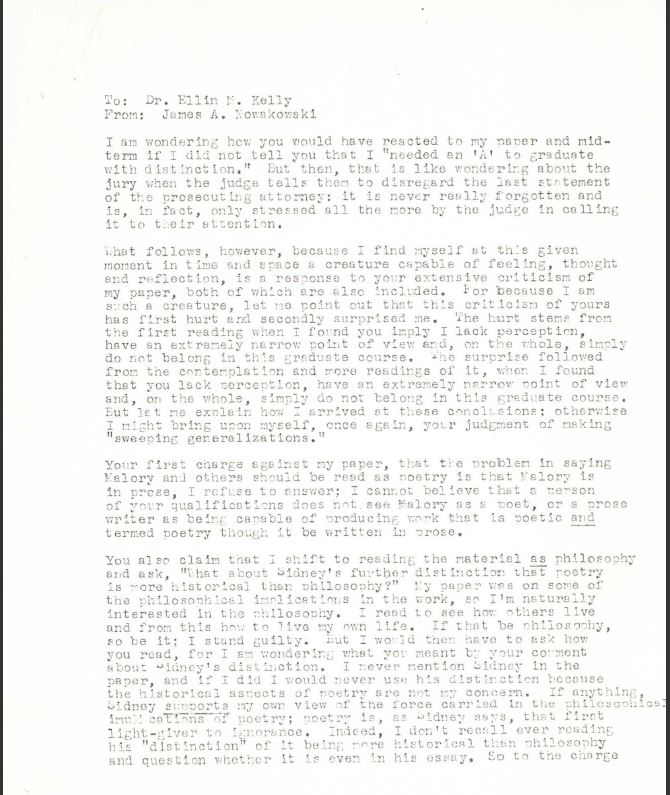

To: Dr. Ellin F. Kelly From: James A. Nowakowski

I am wondering how you would have reacted to my paper and mid-term if I did not tell you that I “needed an ‘A’ to graduate with distinction.” But then, that is like wondering about the jury when the judge tells them to disregard the last statement of the prosecuting attorney: it is never really forgotten and is, in fact, only stressed all the more by the judge in calling it to to-their attention.

What follows, however, because I find myself at this given moment in time and space a creature capable of feeling, thought and reflection, is a response to your extensive criticism of my paper, both of which are also included. For because I am such a creature, let me point out that this criticism of yours has first hurt and secondly surprised me. The hurt stems from the first reading when I found you imply I lack perception, have an extremely narrow point of view and, on the whole, simply do not belong in this graduate course. The surprise followed from the contemplation and more readings of it, when I found that you lack perception, have an extremely narrow point of view and, on the whole, simply do not belong in this graduate course. But let me explain how I arrived at these conclusions; otherwise I might bring upon myself, once again, your judgment of making “sweeping generalizations.”

Your first charge against my paper, that the problem in saying Malory and others should be read as poetry is that Malory is in prose, I refuse to answer; I cannot believe that a person of your qualifications does not see Malory as e poet, or a prose writer as being capable of producing work that is poetic and termed poetry though it be written in prose.

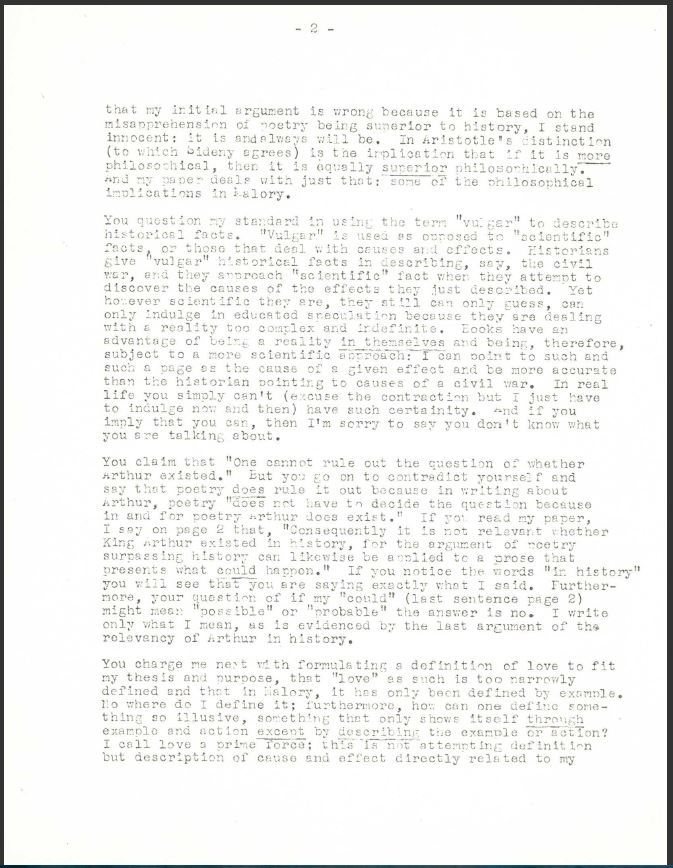

You also claim that I shift to reading the material as philosophy and ask, “What about Sidney’s further distinction that poetry is more historical than philosophy?” My paper was on some of the philosophical implications in the work, so I’m naturally interested in the philosophy. I read to see how others lives and from this how to live my own life. If that be philosophy, so be it; I stand guilty. But I would then have to ask how you read, for I am wondering what you meant by your comment about Sidney’s distinction. I never mention Sidney in the paper, and if I did I would never use his distinction because the historical aspects of poetry are not my concern. If anything, Sidney supports my own view of the force carried in the philosophical implications of poetry; poetry is, as Sidney says, that first light-giver to ignorance. Indeed, I don’t recall ever reading his “distinction” of it being more historical than philosophy and question whether it is even in his essay. So to the charge that my initial argument is wrong because it is based on the misapprehension of poetry being superior to history, I stand innocent; it is and always will be. In Aristotle’s distinction (to which Sidney agrees) is the implication that if it is more philosophical, then it is equally superior philosophically. And my paper deals with just that: some of the philosophical implications in Malory.

You question my standard in using the term “vulgar” to describe historical facts. “Vulgar” is used as opposed to “scientific” facts or those that deal with causes and effects. Historians give ‘vu]gar” historical facts in describing, say, the civil war, and they approach “scientific” fact when they attempt to discover the causes of the effects they just described. Yet however scientific they are, they still can only guess, can only indulge in educated speculation because they are dealing with a reality too complex and indefinite. Books have an advantage of being a reality in themselves and being, therefore, subject to a more scientific approach: I can point to such and such a page as the cause of a given effect and be more accurate than the historian pointing to causes of a civil war. In real life, you simply can’t (excuse the contraction but I just have to indulge now and then) have such certainty. And if you imply that you can, then I’m sorry to say you don’t know what you are talking about.

You claim that “One cannot rule out the question of whether Arthur existed.” but you go on to contradict yourself and say that poetry does rule it out because in writing about Arthur, poetry does rule it out because in and for poetry Arthur does exist. If you read my paper, I say on page 2 that, “Consequently it is not relevant whether King Arthur existed in history, for the argument of poetry surpassing history can likewise be applied to a prose that presents what could happen.” If you notice the words “in history” you will see you are saying exactly what I said. Furthermore, your question of if my “could” (last sentence page 2) might mean “possible” or “probable” the answer is no. I write only what I mean, as is evidenced by the last argument of the relevancy of Arthur in history.

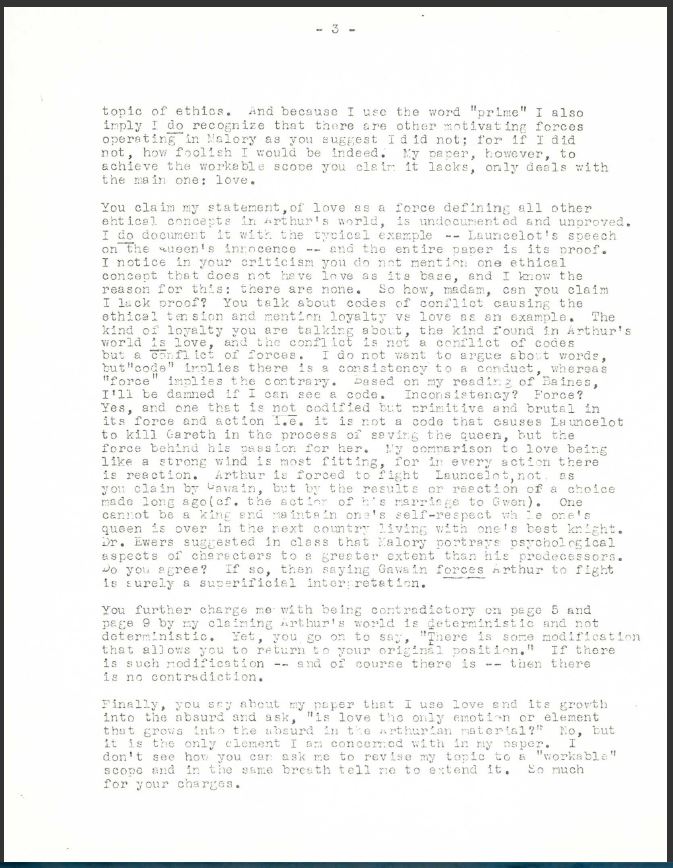

You charge me next with formulating a definition of love to fit my thesis and purpose, that “love” as such is too narrowly defined and that in Malory it has only been defined by example. No where do I define it; furthermore, how can one define something so illusive, something that only shows itself through example and action except by describing the example or action? I call love a prime force; this is not attempting definition but description of cause and effect directly related to my topic of ethics. And because I use the word “prime” I also imply I do recognize that there are other motivating forces operating in Malory as you suggest I did not; for if I did not, how foolish I would be indeed. My paper, however, to achieve the workable scope you claim it lacks, only deals with the main one: love.

You claim my statement, of love as a force defining all other ethical concepts in Arthur’s world is undocumented and unproved. I do document it with the typical example — Launcelot’s speech on the Queen’s innocence — and the entire paper is its proof. I notice in your criticism you do not mention one ethical concept that does not have love as its base, and I know the reason for this: there are none.

So how, madam, can you claim I lack proof? You talk about codes of conflict causing the ethical tension and mention loyalty vs love as an example. The kind of loyalty you are talking about, the kind found in Arthur’s world is love, and the conflict is not a conflict of codes but a conflict of forces. I do not want to argue about words, but “code” implies there is a consistency to a conduct, whereas “force” implies the contrary. Based on my reading of Baines, I’ll be damned if I can see a code.

Inconsistency? Force? Yes, and one that is not codified but primitive and brutal in its force and action i.e., it is not a code that causes Launcelot to kill Gareth in the process of saving the queen, but the force behind his passion for her. My comparison to love being like a strong wind is most fitting, for in every action there is reaction. Arthur is forced to fight Launcelot not as you claim by Gawain, but by the results or reaction of a choice made long ago (cf. the action of his marriage to Gwen). One cannot be a king and maintain one’s self-respect while one’s queen is over in the next country living with one’s best knight. Dr. Ewers suggested in class that Malory portrays psychological aspects of characters to a greater extent than his predecessors. Do you agree? If so, then saying Gawain forces Arthur to fight is surely a superficial interpretation.

You further charge me with being contradictory on page 5 and page 9 by my claiming Arthur’s world is deterministic and not deterministic. Yet, you go on to say, “There is some modification that allows you to return to your original position.” If there is such modification — and of course there is — then there is no contradiction.

Finally, you say about my paper that I use love and its growth into the absurd and ask, “is love the only emotion or element that grows into the absurd in the Arthurian material?” No, but it is the only element I am concerned with in my paper. I don’t see how you can ask me to revise my topic to a “workable” scope and in the same breath tell me to extend it. So much for your charges.

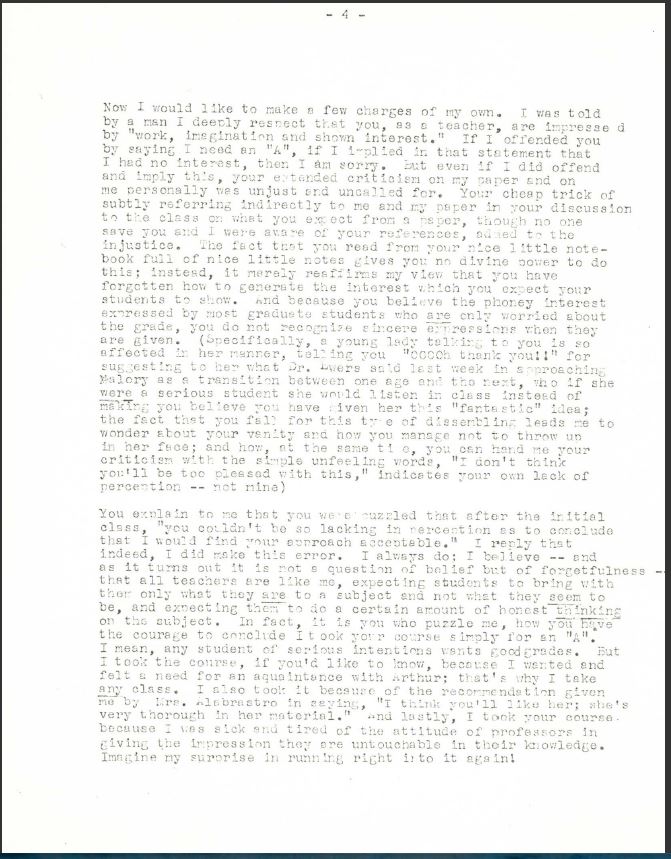

Now I would like to make a few charges of my own.

I was told by a man I deeply respect that you, as a teacher, are impressed by “work, imagination and shown interest.” If I offended you by saying I need an “A,” if I implied in that statement that I had no interest, then I am sorry. But even if I did offend and imply this, your extended criticism on my paper and on me personally was unjust and uncalled for.

Your cheap trick of subtly referring indirectly to me and my paper in your discussion to the class on what you expect from a paper, though no one save you and I were aware of your references, added to the injustice.

The fact that you read from your nice little notebook full of nice little notes gives you no divine power to do this; instead, it merely reaffirms my view that you have forgotten how to generate the interest which you expect your students to show.

And because you believe the phony interest expressed by most graduate students who are only worried about the grade, you do not recognize sincere expressions when they are given. (Specifically, a young lady talking to you is so affected in her manner, telling you, “OOOOh thank you!!!!” for suggesting to her that Dr. Ewers said last week in approaching Malory as a transition between one age and the next, who if she WERE a serious study she would listen in class instead of making you believe you have given her this “fantastic” idea; the fact that you fall for this type of dissembling leads me to wonder about your vanity and how you manage not to throw up in her face; and how, at the same time, you can hand me your criticism with the simple, unfeeling words, “I don’t think you’ll be too pleased with this,” indicates your own lack of perception – not mine).

You explain to me that you were puzzled that after the initial class, “you couldn’t be so lacking in perception as to conclude that I would find your approach acceptable.” I reply that indeed, I did make this error. I always do; I believe — and as it turns out it is not a question of belief but of forgetfulness– that all teachers are like me, expecting students to bring with them only what they are to a subject and not what they seem to be, and expecting them to do a certain amount of honest thinking on the subject.

In fact, it is you who puzzle me, how you have the courage to conclude I took your course simply for an “A.” I mean, any student of serious intentions wants good grades. But I took the course, if you’d like to know, because I wanted and felt a need for an acquaintance with Arthur; that’s why I take any class. I also took it because of the recommendation given me by Mrs. Alabrastro in saying, “I think you’ll like her; she’s very thorough in her material.” And lastly, I took your course because I was sick and tired of the attitude of professors in giving the impression that they are untouchable in their knowledge. Imagine my surprise in running right into it again!

But to continue, you also say that I devote about half my paper to, “a pastiche of sources ranging from Aristotle to Camus which, I assume, is to confound any reader who has not consulted these sources.” This statement leads me to believe that you did not read my paper carefully; I use only three quotations from Camus, and one from Kierkegaard at the end of my paper, all of which certainly does not constitute half. But I use these quotations because they say what I want to say much better than I can. And while it is true I refer to other works, it is not nor ever was with the intention of confounding the reader. I simply bring to the topic what I know, what I’ve become from my study. If you believe I do this to confound anyone, then I can only believe it is because you yourself are confounded.

And as to that nice little word “pastiche,” how dare you imply my writing is a caricature of previous writings! Employing what one knows is not ” pastiche” — it is reasoning. To stand in front of class and read nice little notes is “pastiche.” The papers you will read in this class will be ” pastiches,” jokes, cartoons, ha-ha’s.

But, Dr. Kelly, I am not laughing nor do I intend to laugh. In all seriousness, I say that your implications of my not knowing what graduate study is all about makes me wonder who you think you are dealing with.

Perhaps this feeling on your part is due to the fact that your course is my last one and is, so to speak, an anti-climax for me. I took over the summer the eight hour comprehensive examinations for which I prepared, one might say, most of my adult life. I was very nervous during that time. I passed all four exams, and two of the four I received distinctions on. One distinction — American Literature — was in an area I had not had a course in since my undergraduate study.

Consequently, I must know something about “graduate study” – though my notion may be different than yours. Yet simply because there is a difference gives you no right to imply I do not have a conception of it. Indeed, were I so inclined, I might question your notion of it when that notion involves showing us those nice, pretty slides each week after reading from your nice little notebook.

You say that if I want the “A” I will have to do. some “scrambling” in discovering a “workable scope” for my paper and making it an “exhaustive and comprehensive study of those portions of the text which bear directly upon your topic.” I reply I did do this for the period of time involved. I can say, despite what you believe to be contrary, that I covered-adequately the ethics of -Arthur in 11 pages because I only dealt with its prime motivating force: love. And if you say I make sweeping generalizations, I find nowhere in your criticism a refutation of any of my statements.

Eleven pages and ten weeks necessitates “sweeping generalizations” if I expect to get a total picture of the material. And if I did not do any serious thinking on my topic, or if I did not support my claims, tie generalizations would be erroneous. They are, however, still standing up, so I am consequently led to believe it is merely because I mentioned I want an “A” in your course that I was treated in such a fashion. So be it.

I am submitting my paper — the same one — and as you indicated to me you do not find my work “very distinguished” will submit it nevertheless, your charges having fallen in the same “undistinguished” nook.

_______________________________________________

(scans of the original)

______________________________________________________________________________

The following week after I gave Dr. Kelly my rebuttal to her attack, I received a registered letter from DePaul from Dr. Kelly. It said, “At the present time I am unable to provide an objective grade for you in English 410. Whatever grade I might give you could be construed as the result of either intimidation or prejudice.”

It went on: “To find some reasonable resolution for this dilemma, I asked Dr. Ewers if I could submit your paper to the other professional medievalist on our faculty, Dr. Thomas Murphy. Since you returned the paper to me, I assume it represents your final submission. Before I give the paper to Dr. Murphy for evaluation, I need a written statement from you, agreeing to accept Dr. Murphy’s grade as your grade for the course.”

It closed: “Should you object to this arrangement, I would suggest that you contact Dr. Ewers with any alternative suggestion you may have. I shall retain your paper, the xerox of my comments, and your refutation. In the event that some mutually agreeable solution cannot be reached, I will turn these over to the Dean of the Graduate School for arbitration.”

I remember turning to my wife when I read that letter saying, “Jesus Christ…the Dean of the Graduate School for Arbitration. Just what I need.”

My father had just died. He was 50 years old. I decided I would contact Dr. Ewers and made an appointment. Ewers was the chairperson of the English Department, and I knew her. In fact, she had been a “guest” lecturer in Dr. Kelly’s class one day to talk about Arthur. I thought at the time Dr. Kelly had run out of material.

When I saw down in her office, I said, “This is not what I wanted, this arbitration thing. But did you read my paper and her charges and my rebuttal?”

“Yes,” she said.

“You know if I go along with this Murphy thing, it’s not going to be in my favor, Dr. Ewers,” I told her. “I’m a teacher. I know how teachers are. They stick together like lawyers.”

She smiled. “You know, this is not the first time this has happened in her class. You’re not the first one.”

I felt vindicated. “Then what am I supposed to do?”

“You have to make that decision,” she said. “It is up to you.”

There was silence.

“You know, Jim, when I was lecturing in her class, you were the only one in class I felt I wasn’t reaching,” she said.

“What do you mean?”

“I mean you were the only one I wasn’t getting verbal cues back that you understood what I was talking about. You would look out the window, take some notes, but I didn’t get any positive feedback.”

“That’s my nature,” I said. Then I proceeded to repeat what her lecture was about back to her.

Her eyes widened. “So it’s obvious you’re a smart guy,” she said. “So what made you challenge her?”

“You said it yourself,” I replied. “I’m not the first, and I won’t be the last. I teach underachievers. You can’t fake your passion for learning, and you can’t show slides of your trip to England and call that education, even if you say you traveled over the roads Arthur did.”

There was silence again, and I let it sit for a bit.

“I’ll go with the Murphy thing,” I said. “But you and I both know how it will turn out.”

She smiled again, “I can’t say I do, but I understand. Good luck.”

“So did you like my paper?”

“It was…interesting.”

I smiled and left. “Interesting” is one of the safest words in the English language. You can find Dr. Murphy’s response to my paper in another section of this website.

Hi sir,

I am a twenty-two-year-old recent college graduate from North Carolina (originally from Illinois) who stumbled upon this page. To be honest, I’m not sure who you are or who anyone mentioned in your blog post is — I was just flipping through an old art book, “Georges de La Tour and His World,” that has been sitting on my shelf for years, and I noticed a sticker inside the front cover with the name Ellin M. Kelly and an Evanston, IL address. At 6-something-am (very early for this Gen Z-er), I’ve fallen down an Internet rabbit hole of links related to Dr. Kelly.

All I can say is I’m fascinated by the self-assurance of your rebuttal to your professor’s notes — a kind of boldness and blunt honesty that I can’t imagine from myself — and by the dedication — a level of patience, integrity, and poeticism that I can’t imagine from most of my generation. Nowadays if someone my age received comments from a professor with which they so strongly disagreed, they’d probably rant to their friends, maybe leave a poor review on Rate My Professor and the course evaluation, or at most send the professor an email to express their disappointment.

Anyway, I’m glad I went down that rabbit hole. I was a little sad to see Dr. Kelly’s obituary link come up, but it was nice to read just a little more about who this mystery woman on the sticker was. I hope you’re still alive and doing well. I’m off to read more of your writing now — I’m hooked. God bless 🙂

Hello, and sorry it took me so long to reply to your comment, Angela. I’m glad you went down the rabbit hole too. Many people think Alice fell into her rabbit hole, but the fact is, she jumped in it. Rabbit holes often lead nowhere, but the truth is whenever you jump down one, you learn something. Your generation is a puzzle to my generation; my generation was a puzzle to my parents’ generation. But not really. People are people. What you read and saw something your generation wouldn’t do, well, that’s knowledge through comparison, and is the only way we actually grow. I did what I did because I was confident in my own knowledge and interpretation of the topic. What you read was the truth about an event in my life, a turning point when I made the decision to challenge power, not just with a post or email, but with consequences. It cost me graduating with distinction officially as you read in the entire piece; however, challenging power helped me understand the world and myself a little better. Keep jumping down those rabbit holes!! And thank you for reading it! You might like http://www.readingwithjimmy.com as well.